"Photography takes an instant out of time, altering life by holding it still."

--Dorothea Lange, American photographer, (1895-1965)

A picture is worth a thousand words, as the saying goes, but some photographs can be worth just one heavy handful of potent words - words pregnant with meaning, set in bold with exclamation points and a severe emotional font, like Toxica.

The use of photographic storytelling in political protests and social revolutions has a long history of quiet effectiveness, whether it's Dorothea Lange documenting the plight of the Dust Bowl immigrants or Jeff Widener's shot of the lone protestor at Tiananmen Square. Of course, the brave souls who documented the fire hoses, sit-ins, lynchings and marches of the turbulent Civil Rights era did humanity a tremendous favor. For those of us who were not there or unaware, the photographs tell a very simple story, not just of black and white but of wrong and right.

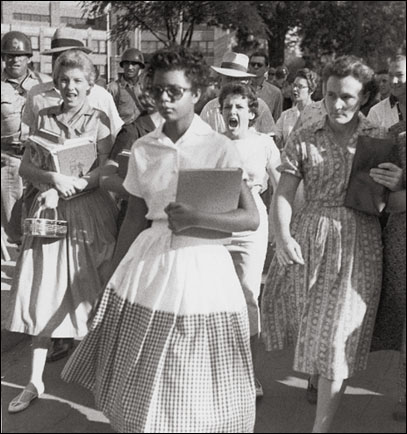

The well-known image of a hateful Hazel Bryan taunting a stony silent (and probably scared to death) black student, Elizabeth Eckford, as both made their way to the front door of Little Rock's Central High is the one that chills me most. (Everyone in the crowd is wearing those lovely Donna Reed dresses of the '50s and when people talk about how idyllic that era was, I just cringe and this image comes to mind.)

The well-known image of a hateful Hazel Bryan taunting a stony silent (and probably scared to death) black student, Elizabeth Eckford, as both made their way to the front door of Little Rock's Central High is the one that chills me most. (Everyone in the crowd is wearing those lovely Donna Reed dresses of the '50s and when people talk about how idyllic that era was, I just cringe and this image comes to mind.)The photograph, taken on September 4, 1957 by Will Counts, is not only iconic (named as one of the 'Top 100 Photographs of the 20th Century by the Associated Press) but it sparked real change, specifically, in the heart and soul of Hazel, the white woman who is the source of racial hatred in the photo.

Years Later, as the photograph became globally infamous, Hazel was forced to deal with the angry young woman she was that day in 1957; she simply could not escape it and was forced to ask herself some hard questions. In a 1998 interview, Hazel explained:

"I am not sure at that age what I thought, but probably I overheard that my father was opposed to integration.... But I don't think I was old enough to have any convictions of my own yet."

After a lifetime of soul searching, Hazel took the difficult first step of contacting Elizabeth to offer a formal apology. Their first meeting - four decades later - was reportedly "awkward" but Hazel was quite sincere and eventually, a real friendship blossomed. And, like all heartwarming tales of modern times, the story concludes with the two women hugging it up on Oprah.

The only reason we know this story today is because just one photographer saw history in action, took aim and pressed a button. In this case, the actual photograph was the lone catalyst, as noted in this 1998 editorial from the Arkansas Democratic-Gazette:

"One of the fascinating stories to come out of the reunion was the apology that Hazel Bryan Massery made to Elizabeth Eckford for a terrible moment caught forever by the camera. That 40-year-old picture of hate assailing grace - which had gnawed at Ms. Massery for decades - can now be wiped clean, and replaced by a snapshot of two friends. The apology came from the real Hazel BryanMassery, the decent woman who had been hidden all those years by a fleeting image. And the graceful acceptane of that apology was but another act of dignity in the life of Elizabeth Eckford."

In a more pro-active approach, the photographs of Chinese artist, Shen Qi, make a silent statement of their own. For starters, he took the liberty of cutting off his left pinky finger to protest the events of Tiananmen Square in 1989. (Somewhere, Van Gogh is grinning ear to ...um ... well ....) Then, he placed a series of photographs in the palm of his own mangled hand, using it as a backdrop, against another backdrop of solid red.

In a more pro-active approach, the photographs of Chinese artist, Shen Qi, make a silent statement of their own. For starters, he took the liberty of cutting off his left pinky finger to protest the events of Tiananmen Square in 1989. (Somewhere, Van Gogh is grinning ear to ...um ... well ....) Then, he placed a series of photographs in the palm of his own mangled hand, using it as a backdrop, against another backdrop of solid red.Some shots are old family photographs, while others depict Chinese propaganda, but it's the image of the lopsided hand that gets you. I found myself staring at the empty space where his finger used to be and pondering the frustration and pain a person has to feel to go to such lengths. Qi's work is sad, brilliant and brave. Most of all, it is important.

Then there's Terry Evans, another great photographer who points her lens at a world that most fly over without a thought: America's prairies. Thanks to my deep love for all things North Dakota, I happen to be aware that this part of the world currently faces turbulent times.

Terry's work has been "primarily an inquiry into the nature of prairie from its native state to its use, abandonment and care." Many of her best shots are taken from the air, where one can almost grasp the expansive beauty and deep loneliness of our nation's midsection. As Terry's bio explains:

"Her intention has been to tell the prairie's stories, past and present, through visible facts and layers of time and memory on the landscape."

I'm especially fond of her series entitled: "Prairie Images of Ground and Sky, 1978-1985." The seemingly-simple photographs inspire me to breathe deep and hum the "America the Beautiful." For some reason, they also make me crave gravy.

Must be a Midwestern thing.

No comments:

Post a Comment